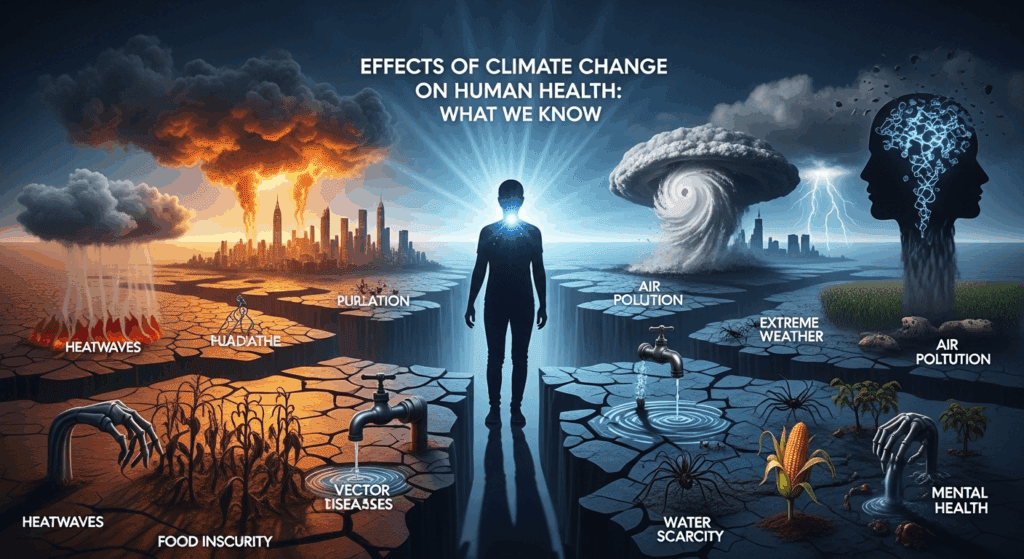

Effects of Climate Change on Human Health: What We Know

Effects of climate change on human health are already being observed around the world, from rising heat-related deaths to expanding ranges of infectious diseases. This article reviews the latest evidence on how changing climate patterns affect human wellbeing, healthcare systems, and communities—and it highlights practical responses policymakers, clinicians, and individuals can pursue to reduce harm and build resilience.

H2: Heat, Extreme Weather, and Direct Health Impacts

Extreme heat and more frequent heatwaves are among the clearest ways the climate crisis affects human bodies and health systems. Rising temperatures increase the risk of heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and worsening outcomes for people with cardiovascular and respiratory disease. Heat waves can also strain healthcare infrastructure, reduce labor productivity, and increase mortality rates, especially when nighttime temperatures remain high and prevent physiological recovery.

- Heat-related Illnesses

Heat exposure triggers a range of clinical conditions from mild heat cramps and syncope to life‑threatening heatstroke. Elderly people, outdoor workers, infants, and those with chronic illnesses are particularly vulnerable. In urban areas, the urban heat island effect amplifies temperature increases, and areas with limited green space face disproportionate risk.

Heat stress also interacts with other health conditions. For example, dehydration and electrolyte imbalances can worsen kidney disease; higher temperatures can increase the metabolic demands on people with heart disease; and some medications interfere with thermoregulation. Early warning systems, community cooling centers, and workplace protections are essential public health tools.

- Extreme Weather Events

Storms, floods, hurricanes, and wildfires have immediate health consequences—injuries, traumatic deaths, and acute exacerbation of chronic illnesses—and longer-term effects from displacement and infrastructure disruption. Flooded hospitals, contaminated water supplies, and interrupted electricity can compromise care for people on dialysis or reliant on medical devices.

Repeated or sequential disasters increase cumulative harm. Communities hit by one extreme event before they recover from the prior event face compounded mental health burdens and loss of social capital. Improving infrastructure resilience and integrating disaster preparedness into health systems reduces both immediate and prolonged harms.

H2: Air Quality, Wildfires, and Cardiorespiratory Health

Air pollution and climate-driven wildfire smoke are key mediators of health impacts. Warmer and drier conditions lengthen wildfire seasons and increase the frequency of large fires, which release fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and toxic gases that travel thousands of kilometers. Poor air quality aggravates asthma, COPD, cardiovascular disease, and is linked to increased mortality.

- Wildfire Smoke and Particulate Matter

Wildfire smoke contains PM2.5, carbon monoxide, and volatile organic compounds that penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream. Short-term exposure increases emergency department visits for respiratory and cardiac events; long-term or repeated exposures are linked to chronic heart and lung disease. Air quality advisories, high-efficiency filtration indoors, and public guidance for evacuation or mask use are critical mitigation measures.

Vulnerable groups—children, older adults, pregnant people, and those with pre-existing respiratory or cardiovascular illness—bear disproportionate burdens. Investing in forest management combined with emissions reduction strategies lowers both fire risk and population exposure.

- Ozone, Pollutants, and Heart Disease

Rising temperatures enhance ground-level ozone formation, worsening smog and respiratory inflammation. Ozone and other pollutants also elevate the risk of hypertension, arrhythmias, and ischemic events. The combined burden of heat and poor air quality can overwhelm emergency services during heatwaves and wildfire episodes.

Public health messaging should integrate air quality, heat advisories, and guidance on safe outdoor activity. Urban planning that reduces vehicle emissions and increases green infrastructure can produce co-benefits—improved air, lower temperatures, and better public health.

H2: Infectious Diseases, Vectors, and Waterborne Illnesses

Climate change alters ecosystems, vector distributions, and water systems—shifting the epidemiology of many infectious diseases. Warmer temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and extreme events can expand the geographic range and seasonality of vector-borne diseases (mosquitoes, ticks), increase waterborne outbreaks, and complicate food safety.

- Vector Range Shifts

Mosquitoes that transmit dengue, chikungunya, Zika, and malaria are sensitive to temperature and humidity. As climates warm, some species expand into higher altitudes and latitudes, exposing new populations to disease. Tick-borne illnesses such as Lyme disease are also shifting, with longer transmission seasons and increased case counts in some regions.

Surveillance, vector control, vaccines where available, and public awareness campaigns are essential. Health systems must adapt laboratory and clinical capacity to recognize diseases that were previously rare in certain areas. Integrated vector management that combines environmental controls, community engagement, and targeted insecticide use can reduce transmission risk.

- Waterborne and Foodborne Diseases

Heavy rainfall and floods can contaminate drinking water with pathogens (e.g., cholera, norovirus) and increase the risk of gastrointestinal outbreaks. Conversely, droughts can concentrate pathogens and pollutants in limited water supplies. Rising temperatures may also favor growth of harmful algal blooms and foodborne pathogens like Salmonella, increasing illness risk.

Strengthening water and sanitation infrastructure, ensuring access to safe drinking water, and rapid detection systems are critical. Climate-smart agricultural practices and cold-chain resilience reduce food safety risks, while community education on hygiene and safe food handling mitigates immediate exposures.

H2: Mental Health, Displacement, and Social Determinants

Health impacts of climate change are not only physical; they deeply affect mental health, social stability, and the determinants of health such as housing, income, and access to care. Chronic stress, grief over environmental loss, and trauma from disasters contribute to rising rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Climate Anxiety and PTSD

Younger generations frequently report climate anxiety—a persistent worry about future climate harms. Acute events like hurricanes or wildfire evacuations can produce PTSD, while slow-onset changes (sea-level rise, loss of livelihoods) can erode mental wellbeing over time. Mental health services often lack capacity or funding to manage these growing needs.

Community-based interventions, culturally appropriate counseling, and integration of mental health into disaster response improve outcomes. Building social cohesion and restoring local environments (e.g., community greening) can provide therapeutic benefits and strengthen resilience.

- Migration, Displacement, and Health Services

Climate-related displacement—temporary or permanent—creates complex health challenges. Displaced populations may face overcrowded shelters, interrupted care for chronic diseases, increased exposure to infectious diseases, and barriers to mental healthcare. Host communities can experience strain on services and social tensions.

Planning for managed retreat, improving shelter standards, and ensuring continuity of care for displaced persons (medication access, immunization) are essential public health priorities. Equitable policies that protect the rights and health of migrants and displaced persons reduce long-term harms.

H2: Vulnerable Populations and Health Equity

Climate impacts are not evenly distributed. Social, economic, and political factors determine vulnerability and adaptive capacity. Children, older adults, low-income communities, frontline workers, and Indigenous peoples disproportionately experience the negative health effects of climate change. Addressing equity is central to effective health-oriented climate action.

- Children, Elderly, and Chronic Conditions

Children are more susceptible to heat stress, respiratory illnesses, and the developmental impacts of environmental toxins. The elderly face increased mortality during heatwaves and may have mobility limitations that impede evacuation. People with chronic conditions (diabetes, heart disease, mental illness) often require uninterrupted access to medications and services that can be disrupted during disasters.

Targeted interventions—cooling strategies for schools and long-term care facilities, priority communications for at-risk populations, and continuity plans for medication—save lives. Health practitioners should proactively identify and support patients at higher climate-related risk.

- Low-income Communities and Indigenous Peoples

Low-income neighborhoods often have less green space, poorer housing quality, and reduced access to healthcare, compounding exposure to heat, pollution, and flooding. Indigenous communities frequently experience disproportionate environmental change due to proximity to vulnerable ecosystems and historical marginalization.

Policies that center community voices, provide resources for local adaptation, and protect land and cultural practices can promote health equity. Climate solutions that incorporate justice—such as distributed clean energy, improved housing, and workforce protections—yield both health and social benefits.

H2: Adaptation, Mitigation, and Health System Responses

Health systems must anticipate and respond to climate-driven health threats while reducing their own carbon footprints. Mitigation (reducing greenhouse gas emissions) and adaptation (preparing for impacts) are complementary strategies that produce immediate and long-term health gains.

- Public Health Interventions and Early Warning

Early warning systems for heatwaves, air quality alerts, and vector surveillance save lives by enabling timely protective actions. Vaccination campaigns, strengthened laboratory networks, and targeted outreach to at-risk communities reduce disease burden. Emergency preparedness must include supply chain resilience for medicines, oxygen, and power.

Health workforce training on climate-related health issues improves diagnosis and management. Cross-sectoral collaboration—between health, meteorology, urban planning, and emergency management—creates cohesive responses that protect communities.

- Policy, Urban Planning, and Co-benefits

Policies that reduce fossil fuel use, promote active transport, and increase urban green spaces deliver co-benefits: lower emissions, improved air quality, increased physical activity, and better mental health. Hospitals and clinics can reduce their environmental impact through energy efficiency, waste reduction, and sustainable procurement.

Investing in climate-resilient infrastructure—flood-proof hospitals, decentralized energy systems, and telemedicine—safeguards care continuity. Health professionals and institutions are influential advocates for policies that protect health through climate action.

Table: Selected Climate Drivers and Associated Health Consequences

| Climate Driver | Primary Health Outcomes | Example Regions at Risk | Timeframe/Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rising temperatures / heatwaves | Heatstroke, cardiovascular events, increased mortality | Urban areas, Southern Europe, South Asia, parts of US | Increasing frequency and severity (ongoing) |

| Wildfires & smoke | Exacerbation of asthma, COPD, ischemic heart disease | Western US, Australia, Mediterranean | Longer fire seasons; more intense fires |

| Changing precipitation / floods | Waterborne disease outbreaks, injuries, mold-related respiratory illness | Low-lying regions, river valleys, coastal cities | More extreme rainfall events; flood risk rising |

| Vector habitat shifts | Increased dengue, malaria, Lyme disease | Tropical highlands, temperate regions at higher latitudes | Expansion seasonally and geographically |

| Sea-level rise, storms | Displacement, mental health impacts, infrastructure loss | Small island states, coastal cities | Gradual but accelerating; severe storms more frequent |

H2: Practical Steps for Individuals, Communities, and Health Systems

Addressing health impacts requires action at multiple levels. Individuals can reduce personal risk; communities can build local resilience; health systems and governments can implement large-scale policies.

- Individual actions:

- Stay informed of local heat and air quality advisories.

- Prepare a medication and emergency kit; know evacuation routes.

- Reduce personal emissions (active transport, energy efficiency).

- Community and municipal actions:

- Increase tree canopy and urban green spaces.

- Establish cooling centers and community emergency plans.

- Improve public transit and reduce traffic emissions.

- Health system and policy actions:

- Integrate climate risk into health planning and surveillance.

- Invest in resilient infrastructure and renewable energy for facilities.

- Advocate for climate policies that prioritize public health.

These measures create multiple co-benefits: cleaner air, safer communities, and stronger local economies. Prevention and preparedness are often more cost-effective than responding to health crises after they occur.

FAQ — Questions & Answers

Q: How immediate are the health effects of climate change?

A: Both immediate and long-term effects are already present. Heatwaves, wildfires, and storms cause immediate harm, while shifts in disease patterns and social determinants unfold over years to decades.

Q: Which populations are most at risk?

A: Children, older adults, pregnant people, those with chronic illnesses, low-income communities, frontline workers, and Indigenous peoples are among the most vulnerable due to exposure, sensitivity, and limited adaptive capacity.

Q: Can mitigation measures improve health now?

A: Yes. Reducing fossil fuel use lowers air pollution and associated respiratory and cardiovascular disease. Urban greening reduces heat and improves mental health—these are near-term co-benefits.

Q: What can clinicians do today?

A: Clinicians can screen patients for climate-related risks, counsel on heat and air quality precautions, advocate for resilient health services, and participate in community preparedness planning.

Q: Are some regions safer than others?

A: Risks vary by region, but no area is immune. High-latitude regions may initially see fewer heat-related deaths but face new vector-borne disease risks. Coastal and low-lying areas face acute risks from sea-level rise and storms.

Conclusion

The evidence is clear: the effects of climate change on human health are multifaceted, spanning direct physical harms from heat and storms to air quality deterioration, infectious disease shifts, and profound mental health and social impacts. Responses that combine mitigation and adaptation—rooted in equity and robust public health practice—offer the best path to protect current and future generations. Health professionals, policymakers, communities, and individuals each have roles to play: from reducing emissions and strengthening surveillance to improving infrastructure and supporting vulnerable populations. The time to act is now; proactive measures save lives, lower healthcare costs, and create healthier, more resilient societies.

Summary (English)

This article synthesizes current knowledge about the effects of climate change on human health. It covers direct impacts like heat-related illness and injury from extreme weather, indirect effects from degraded air quality and wildfires, shifts in vector-borne and waterborne diseases, and the mental health and social consequences of displacement and chronic environmental change. Vulnerable populations—children, the elderly, low-income and Indigenous communities—face disproportionate risks. Effective responses combine mitigation (emissions reductions) with adaptation (early warning systems, resilient infrastructure, public health interventions) and prioritize equity. Practical steps at individual, community, and health-system levels deliver immediate co-benefits for health while reducing long-term climate risks.